Guest Post by Madelyn Sharples

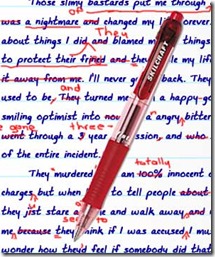

My memoir, Leaving the Hall Light On: a Mother’s Memoir of Living with Her Son’s Bipolar Disorder and Surviving His Suicide consists of a mix of prose, poetry, and photos. And if I could have put music into it I would have.

I originally dreamed about publishing a memoir in poems. I had a finished poetry manuscript early on and since poetry came out almost miraculously from my pen soon after my son died, I thought telling his and my story in poems would be most appropriate.

But I was soon convinced the poems could not stand-alone. My book would lack the details, characterization depth, and the thoughts and feelings of my husband Bob and surviving son Ben that were necessary in the telling of our whole family’s story. The poems provided the chapter themes and emotional impact, the prose provided the details and descriptions, and the photos helped to make the story seem more real.

Early on my son Ben introduced me to a former literary agent who asked to read the poetry manuscript. After her reading she suggested I use the order of the poems as a way to organize my book’s chapters. And that organization stayed mostly intact in the final book manuscript. This young woman also generously gave me writing prompts that helped me flesh out my story in prose. I worked with her in developing the first draft of my memoir for about a year.

As I began to introduce more prose into the manuscript, using my huge supply of journal entries, pieces I wrote in various writing classes, and my advisor’s wonderful writing prompts, I formed chapters each starting with a poem. Then I began to worry that interested agents would reject my book because of the poetry. That concern was not unfounded. As I looked for appropriate agents I found more and more who did not want to be involved in poetry books in any way. I even work-shopped the book and was advised by my instructor to take the poems out.

I also remembered the words of a good friend. She told me no one had the right to tell me that I had to take something out of my book if I, the author, felt it belonged in it. So, I kept the poems in although I didn’t mention their existence in my query letters. I thought I’d discuss the poetry later if it ever came up. Even then I was still waffling about leaving them in or taking them out.

Although I never found an agent to represent my book, I happily contracted with a small traditional press. My publisher asked me to revise my book in many ways, but her only suggestion about the poetry in the book was that I should add more. She resonated with my final decision to include poetry in my memoir.

Madeline’s mission since the death of her son is to raise awareness, educate, and erase the stigma of mental illness and suicide in hopes of saving lives. She and her husband of forty plus years live in Manhattan Beach, California, a small beach community south of Los Angeles. Her younger son Ben lives in Santa Monica, California with his wife Marissa. Click to visit Madeline’s blog, Choices, and on Red Room.com.

Read my Amazon.com review of Leaving the Hall Light On.

Write now: if you write poetry, find a poem or few and write a narrative version of the story they tell. Those like me, who lack the poetry gene or muse, can find a photo and do the same exercise.